By Michael Graves

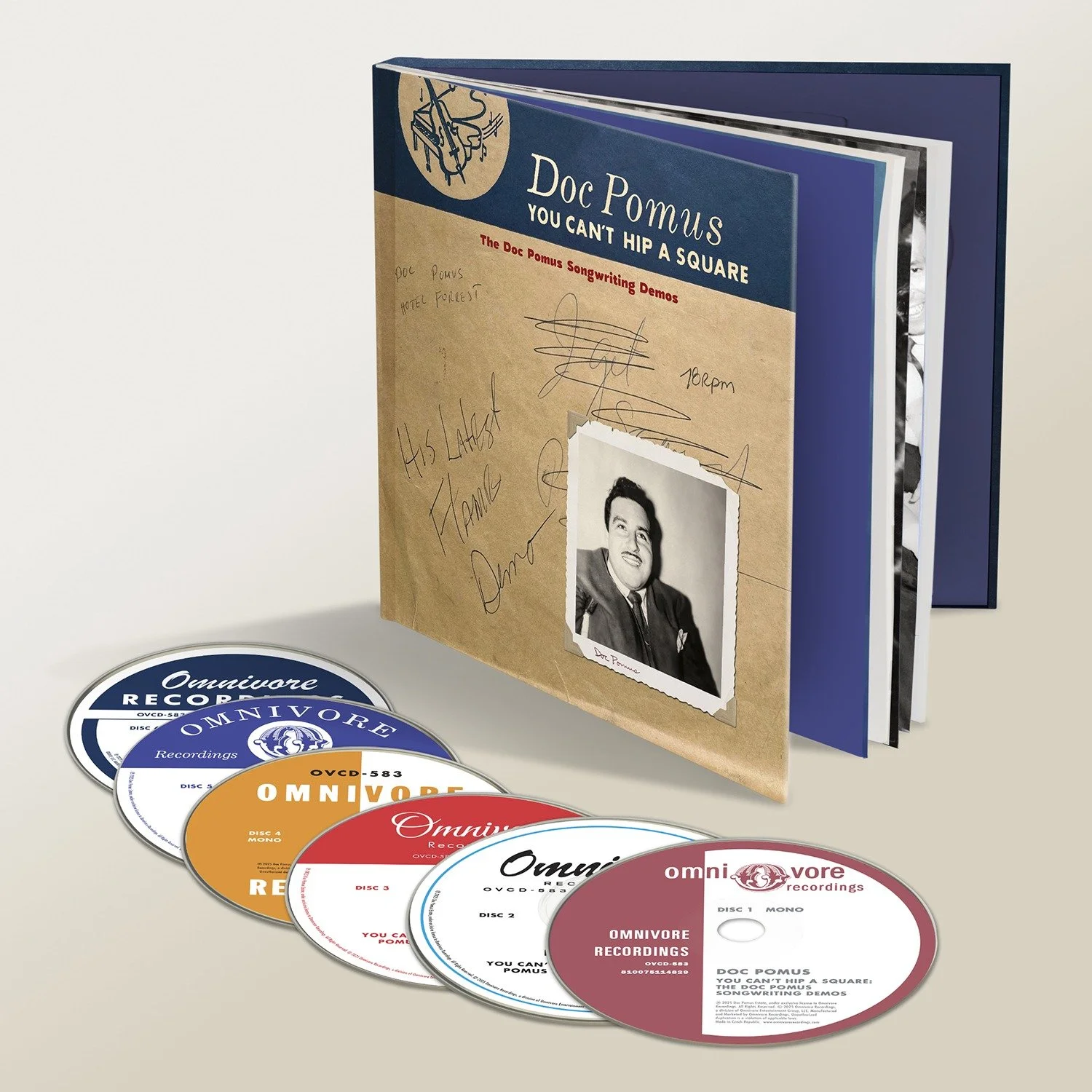

On August 15, 2025, Omnivore Recordings released Doc Pomus – You Can’t Hip A Square: The Doc Pomus Songwriting Demos. The project had been quietly taking shape for well over a year. What follows is a look behind the scenes at how it came together — slowly, imperfectly, and often against expectations. Because things almost never go as planned.

Before diving into acetates, noise floors, and restoration techniques, it’s worth stepping back for a moment to consider the life of a song. How an idea, sung into a tape recorder or scratched into a lacquer disc, can travel decades forward in time and still feel alive.

That clip represents just one song in Doc Pomus’ vast catalog. You already know many of the others: “Save The Last Dance For Me,” “This Magic Moment,” “A Teenager In Love,” and the Elvis recordings “Viva Las Vegas,” “Little Sister,” and “Suspicion,” among hundreds more. These songs have endured not just because they were hits in the past, but because they continue to speak to listeners today and have passed into the realm of what we consider standards.

A Songwriter’s Songwriter

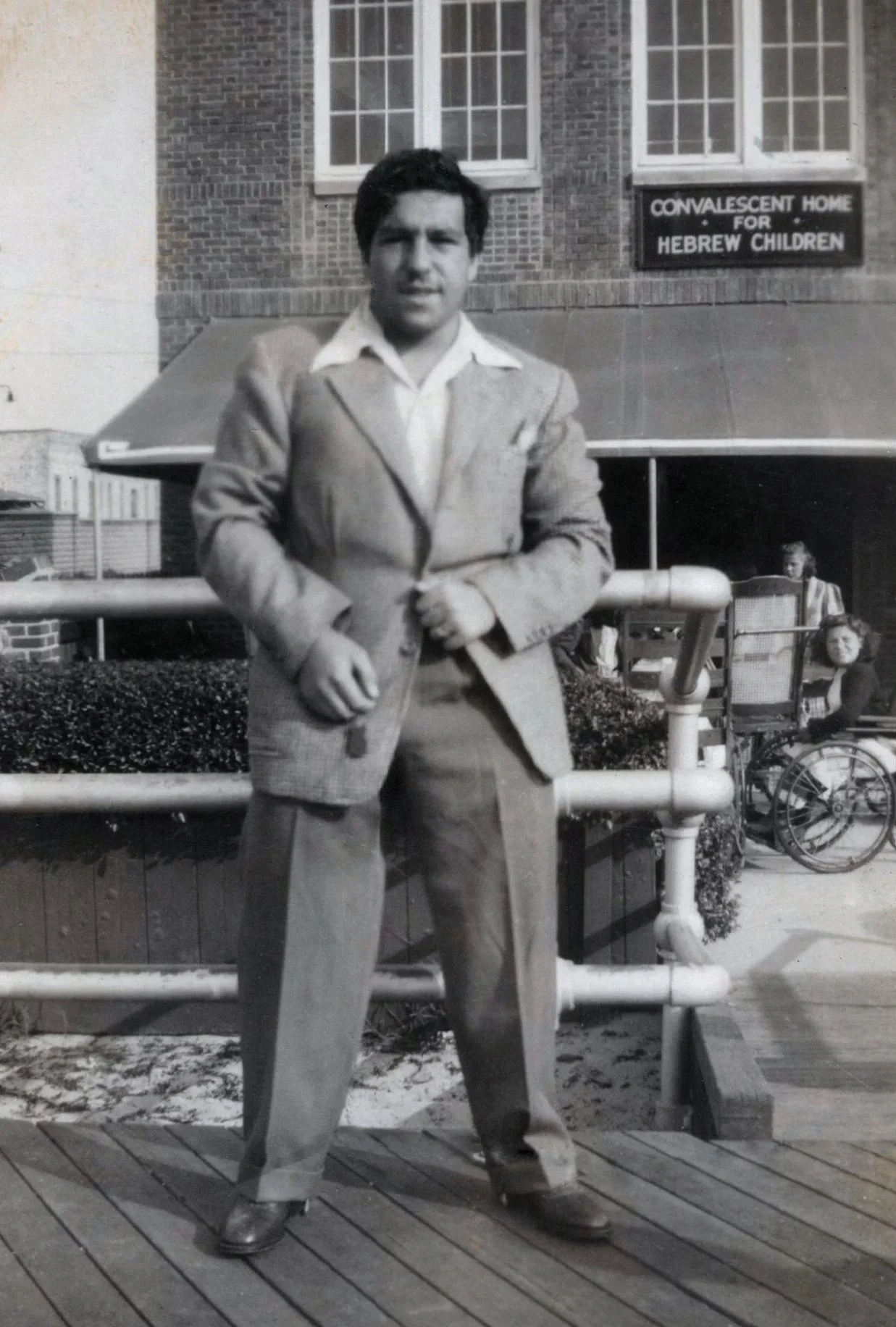

Doc Pomus

Doc Pomus, born Jerome Felder in June of 1925, was a songwriter’s songwriter in the truest sense. Though he began as a blues singer, his lasting legacy came through the songs he wrote for others. Over the course of his life, he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and the Blues Hall of Fame — a rare trifecta that hints at both the breadth and depth of his work.

Doc contracted polio as a child and lived with its effects for the rest of his life. He moved through the world first with braces and crutches, later in a wheelchair. He sang in New York’s African-American clubs and recorded for labels like Chess, Savoy, and Atlantic. In the early 1950s, he turned increasingly toward songwriting, and artists began recording his work almost immediately. “Lonely Avenue,” recorded by Ray Charles, marked a turning point.

After marrying in 1957 and starting a family, Doc stepped away from performing entirely and committed himself to songwriting — not as a creative retreat, but as a way to build a stable life through his craft.

Mort Shuman and Doc Pomus

His most enduring partnership came with Mort Shuman, who entered Doc’s life while dating Pomus’ younger cousin. Mort was younger, full of raw talent, and acutely aware of what young listeners were responding to. Doc recognized that instinct and took him under his wing. Together, they wrote an extraordinary body of work.

Over the course of his career, Doc also collaborated with Phil Spector, Ellie Greenwich, Bette Midler, Dr. John, and Lieber & Stoller. John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon, and Lou Reed counted themselves as admirers. Dylan, in particular, held Doc in such esteem that he dedicated his most recent book to him.

For those wanting to go deeper, Doc’s daughter Sharyn Felder produced the documentary AKA Doc Pomus, which fills in many of the remaining chapters.

The Project Takes Shape

In early 2024, my friend and longtime collaborator Cheryl Pawelski told me the Doc Pomus project was coming together. Much of the source material we would be working from lived on Doc’s original acetates — fragile, irreplaceable artifacts that were never meant to survive this long.

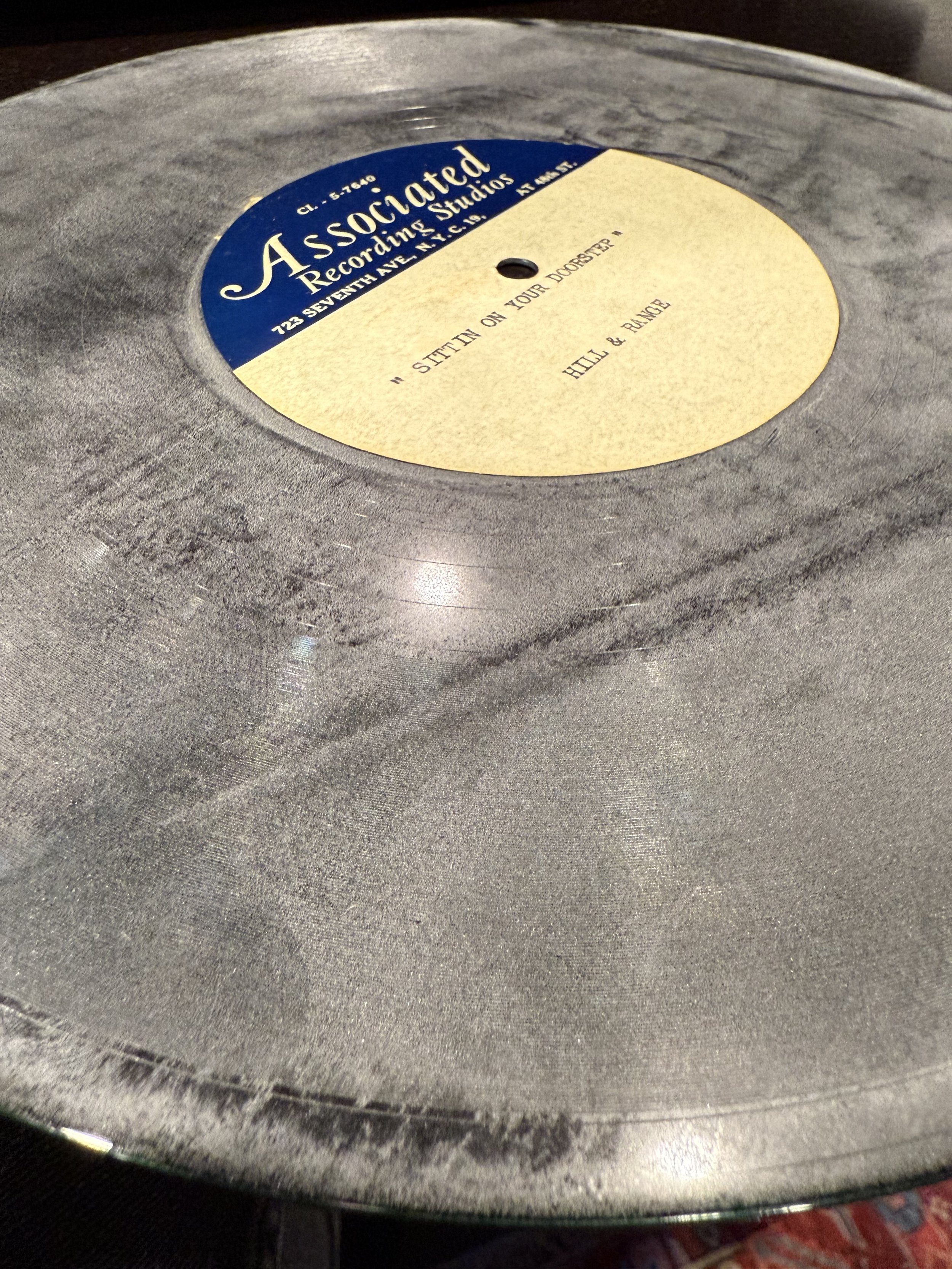

Original Viva Las Vegas acetate

For anyone unfamiliar, acetates are lacquer-coated discs — often aluminum, sometimes glass or cardboard — onto which sound is cut directly, in real time. They go by many names: acetates, lacquers, dub plates, instantaneous recordings. They look like records, and they can be played immediately. That immediacy made them perfect for songwriters like Doc, who could hand them off to a potential client the moment it was recorded.

When treated carefully and restored properly, those discs can sound every bit as good as a master tape.

The Pomus estate, overseen by Sharyn Felder and her husband Will Bratton in New York, held more than 300 of these original acetates. Shipping them across the country wasn’t something anyone felt comfortable doing. When Cheryl raised the concern, I suggested we bring the studio to them.

Cheryl Pawelski transporting valuable cargo.

After working through the logistics, we decided to set up in a hotel and transfer all of the acetates there. I estimated five days to complete the transfers, with help from Cheryl and both of our wives. Joy Graves is no stranger to acetate preservation — she’s handled hundreds here at Osiris Studio. Cheryl would take detailed notes on each disc, and her wife Audrey Bilger would assist wherever needed.

In August 2024, we booked a hotel suite near Sharyn and Will, to minimize transport of the discs, and set up shop.

At first, everything moved smoothly.

Then the acetates began to remind us what they are.

Working Against Time and Decay

Acetates can be challenging. Aluminum bends easily. Lacquer cracks, flakes, and quietly deteriorates. A stylus can lose the groove with the slightest imperfection.

To navigate this, I use a thumb technique — something I’ve relied on for years when dealing with warped or damaged discs. My thumb becomes a shock absorber, applying just enough pressure to keep the stylus seated while allowing it to move inward as the disc spins. At 78 RPM, that inward motion happens quickly. Misjudge it, and the “correction” will cause the record will skip as well.

Palmitic acid buildup

Palmitic acid removed

removing Palmitic Acid

We use a mixture of distilled water and two types of Tergitol (.25 parts Tergitol 15-S-3 and .25 parts Tergitol 15-S-9 per 100 parts distilled water). Tergitol is a mild non-ionic surfactant that lowers water’s surface tension and dissolves palmitic acid safely. We’ve used this mixture for over 25 years on countless priceless acetates and shellac discs with excellent results.

One of the most common problems we encountered was palmitic acid — a white, waxy residue that forms as lacquer decays. It often looks like mold, but it isn’t. Left untreated, it renders a disc nearly unlistenable. Thankfully, it cleans up well.

Even after cleaning, another issue emerged. As I listened, the sound would slowly darken. High frequencies disappeared. Distortion crept in. The stylus was getting dirty — not from any debris left after cleaning, but from the lacquer itself, which was breaking down and collecting on the tip.

The only solution was careful listening. The moment the sound shifted, I lifted the tonearm, cleaned the stylus, and dropped it back a few seconds earlier. Over and over again. The final transfer would later be spliced together in the studio.

Here’s what that sounds and looks like.

And the spliced version.

In the end, we had more than 130 fragmented WAV files that needed to become coherent performances again.

Here’s one more transfer. This particular acetate should have been played at 78 RPM, but because it was bent so severely, causing the lacquer to flake off, the only way to keep the stylus in the groove was to play it at 33⅓ RPM.

This recording didn’t make the final release. But restoration often works this way — you go all the way through the process just to understand what you have.

The extended time it was taking to play the acetates completely disrupted my original time estimates. We only had five days booked, and extending wasn’t possible. Then, three days in, Joy tested positive for COVID. We decided the safest option was for Joy and me to quarantine in our room and continue working — without Cheryl and Audrey’s assistance.

Somehow, we finished all 300+ transfers.

Back in Los Angeles, I tested positive as well. This is where Jordan McLeod enters the story. Jordan has worked with us at Osiris Studio since 2020 and is one of the finest restoration engineers I know. I explained what we were dealing with and handed him a mountain of work.

At that point, we were still discovering what we had. Many acetates hadn’t been heard in decades. The transfers needed to be listenable before the producers could even begin making decisions. Preservation and discovery were happening simultaneously.

Restoration as Craft

Automated tools are only a starting point. Real restoration happens manually, inside a spectrogram editor, one gesture at a time. Across this project, two techniques dominated the work: smoothing unstable noise floors and preserving transients — what we call Transient Saving.

Sputtering and Hissing Noise — “Moving Day Blues”

After de-clicking, underlying noise becomes more apparent and draws attention away from the music.

The goal isn’t silence, but consistency — a noise floor that fades into the background of the listener’s perception. Here’s the same section after manual noise leveling.

All of this noise must be manually highlighted and adjusted until it becomes visually and sonically consistent. The goal is for the noise to disappear into the background of the listener’s mind.

This consistency also matters for spectral de-noising. This type of broadband noise reduction works best on an even noise floor. Inconsistent noise creates artifacts — the brittle, artificial kind that remind you a computer is involved. We avoid those at all costs.

Transient Saving — “Book Of Time”

Transient Saving is a technique I developed around 2014. It’s about protecting the life of a performance. Guitar plucks, drum hits, claps — these are the moments that give a recording energy. De-clicking removes clicks, but it often removes those transients too. Have a listen to the original transfer and notice the transients of the guitar, along with the clicks and pops:

After de-clicking, the clicks are gone, but so are transients. Here is the song after it has been de-clicked, listen again for transients of the guitar — they’ve been removed and the recording sounds dull and lifeless now.

The technique we use is to separate the transients by having the delta of the de-clicker playing on another track in parallel. Below, the top track is the original audio, de-clicked, and the bottom track are the transients along with some clicks and pops. We also use a noise gate on the saved transients track to help isolate the low level surface noise from the louder transients and clicks.

Here’s the transients track isolated. Notice you can hear the guitar plucks in there that we want to save.

As mentioned before, there are still loud clicks alongside the transients, but not as many. Now it’s just a matter of manually separating the good from the bad to ultimately recover the lost transients.

There is no automation for this. No AI. Just listening, editing, and time. Across this project, more than 160 songs required this level of care. Jordan spent over 350 hours restoring these recordings.

Mastering, Interrupted

The project was always conceived as a multi-disc set, each disc shaped around a theme. One disc — songs Doc pitched to Elvis — would also be released as a standalone LP for Record Store Day. That became my first mastering deadline.

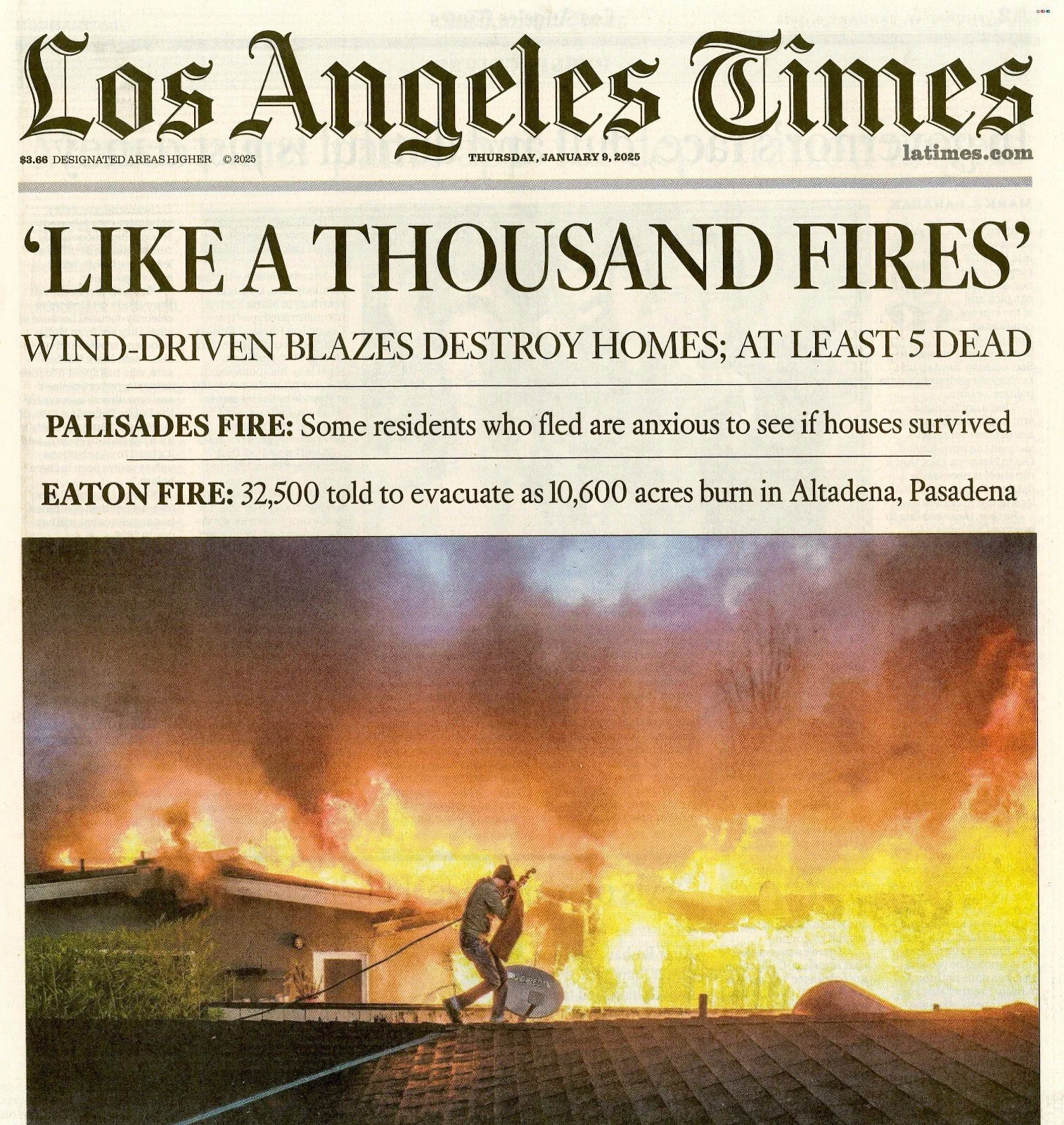

I finished mastering that disc on the evening of January 7th. Shortly afterward, a neighbor posted about a fire in the San Gabriel Mountains behind our home in Altadena. This was the view from our backyard.

We evacuated that night, assuming we’d return in the morning. We didn’t.

The Eaton Fire consumed Altadena over the next several days, Alongside the Palisades Fire, it became one of the worst fire events in U.S. history. It would take three days before we learned that our home and studio had survived. Many others, including Cheryl and Audrey’s, did not.

There’s a limit to how much live news coverage of wildfires destroying your community one can take. I wanted to stay informed, to understand what was happening, but at a certain point I needed an escape. Music has always been a refuge for me, and somewhere in the back of my mind I knew the deadline for the Elvis disc was approaching.

As devastated as Joy, Cheryl, Audrey, and I were, we needed something positive to focus on. It might seem strange to worry about a project deadline while something so catastrophic was unfolding, but events like the Eaton Fire leave you with no agency at all. There is nothing you can do to affect the outcome.

What I did have control over was finishing this record. And after all the work that had gone into it — months of transfer, restoration, and care — that sense of purpose mattered more than ever.

I set up a makeshift studio in our hotel room and relied on my trusted in-ear monitors to make final checks. Equally important was Jordan’s review of everything in his mastering room in Nashville. A few adjustments were made, and the masters were delivered.

Viva Doc Pomus: Songs for Elvis (The Demos) was released for Record Store Day 2025.

We were finally able to return to the studio in mid-February, and I completed the remaining five discs under somewhat normal conditions. Doc Pomus – You Can’t Hip A Square: The Doc Pomus Songwriting Demos was released on August 15, 2025 to very positive reviews.

On November 7, 2025, the boxed set received a GRAMMY nomination for Best Historical Album.